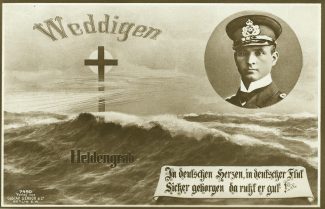

( 2a) Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen. 1882-1915.

H.M.S. Aboukir. H.M.S. Hogue. H.M.S. Cressy.

Kapitänleutnant Otto Eduard Weddigen.

On 22 September 1914, one thousand four hundred and fifty nine men died in the North Sea. Four of the men killed had links to Benfleet and Canvey Island.

BENFLEET.

STANLEY MOOR CHILES. Service No. 210506.

Rank. Leading Seaman.

Service. Royal Navy.

Unit Text. H.M.S. Aboukir.

Son of. Walter Chiles, and the late Mary Chiles, of Melcombe Road. Benfleet.

Memorial Ref. Chatham Naval Memorial. Kent.

CANVEY ISLAND.

ADOLPHUS SAMUEL SMITH. Service No. 220809.

Rank. Leading Signalman.

Service. Royal Navy.

Unit Text. H.M.S. Aboukir.

Son of. Emily Sorrell (formally Smith), of Fobbing. Essex.

Memorial Ref. Chatham Naval Memorial. Kent.

ARTHUR JENNINGS. Service No. 305498.

Rank. Stoker 1st Class.

Service. Royal Navy.

Unit Text. H.M.S. Aboukir.

Memorial Ref. Chatham Naval Memorial. Kent.

WILLIAM THOMAS EASTERBROOK. Service No. 206711.

Rank. Able Seaman.

Service. Royal Navy.

Unit Text. H.M.S. Hogue.

Memorial Ref. Plymouth Naval Memorial. Devon.

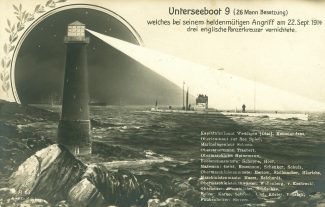

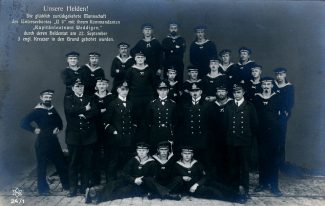

They were without any destroyer escort while patrolling an area known as the Broad Fourteens when they were spotted by Kapitänleutnant Otto Eduard Weddigen, in command of German Submarine U9.

From that day on much has been written about the events that killed so many. The following is an extract from the memoirs of Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen, written in 1914. “I am 32 years old and have been attached to the submarine flotilla and have been most interested in that branch of the navy. At the outbreak of the war our undersea boats were rendezvoused at a series of harbours on our coast of the North Sea. I was married on 16 August 1914 at the home of my brother in Wilhelmshaven to my boyhood sweetheart, Miss Prete of Hamburg. My bride and I wanted the ceremony to take place at the appointed time, and it did, although within twenty-four hours thereafter I had to go away on a venture that gave a good chance of making my new wife a widow.

I was soon cruising off the coast of Holland. I had been lying in wait there only a few days before the morning of 22 September arrived, the day on which I fell in with my quarry. I had sighted several ships during my passage but they were not what I was seeking. English torpedo boats came within my reach but I felt there was bigger game further on.

It was ten minutes after 6 on the morning of last Tuesday and I had been going ahead partly submerged with about five feet of my periscope showing. Almost immediately I caught sight of the first cruiser and two others. I submerged completely and laid course so as to bring up in the centre of the trio. They were near enough for torpedo work but I wanted to make my aim sure, so I went down and in on them. I soon reached what I regarded as a good shooting point. I then loosed one of my torpedoes at the middle ship. I discovered that the shot had gone straight and true striking the ship under one of her magazines, which in exploding helped the torpedoes work of destruction. I later learned that the ship was the Aboukir. She had been broken apart and sank within minutes. The Aboukir had been stricken in a vital spot and by an unseen force; that made the blow all the greater. Her crew were brave and even with death staring them in the face kept to their posts, ready to handle their useless guns.

I could see the Cressy and Hogue, turn and steam full speed to their dying sister. Soon, the other two English cruisers learned what had brought about the destruction so suddenly. I sent a second charge at the nearest oncoming vessel, which was the Hogue. The English were playing my game. The attack on the Hogue went true. She lay wounded and helpless on the surface before she heaved, half turned and sank.

The third cruiser, Cressy, knew the enemy was upon her and she sought as best she could to defend herself. She stood her ground as if more anxious to help the many sailors who were in the water than to save herself. When I got within a suitable range I sent away my third attack. This time I sent a second torpedeo after the first to make the strike doubly certain. Both torpedoes went to their bulls-eye. At once she began sinking by her head, then careened far over, all the while her men stayed at the guns looking for their invisible foe. They were brave and true to their country’s traditions. Then she suffered a boiler explosion and turned turtle. With her keel uppermost she floated until the air got out from under her and she sank with a loud sound, as if from a creature in pain. The whole affair had taken less than one hour.

Having done my appointed work, I set course for home. I reached the home port on the afternoon of the 23rd and on the 24th went to Wilhelmshaven to find that news of my effort had become public. I then learned that my little vessel and her brave crew had won the plaudit of the Kaiser, who conferred each of my co-workers the Iron Cross of the Second Class and upon me the Iron Cross First and Second Class.”

In the space of one hour, forty-nine days after the start of World War 1, the Royal Navy lost three ships and 1549 men. For the majority of the men, their grave is the sea. Ten bodies, five from H.M.S. Aboukir, four from H.M.S. Cressy and one from H.M.S. Hogue were recovered from the sea and taken to The Hague General Cemetery in the Netherlands. Eleven bodies, five from H.M.S. Aboukir, three from H.M.S. Cressy and three from H.M.S. Hogue, were also recovered from the sea and taken to ‘s Gravenzande General Cemetery in the Netherlands. In those cemeteries their bodies were either buried or their names engraved on a Special Memorial.

Kapitänleutnant Weddigen continued service with the submarine and on 15 October 1914 he torpedoed H.M.S. Hawke. She sank in a matter of minutes taking with her 527 men. On 12 March 1915 he sank three British Steamships, the Andalusian, Indian City and Headlines. However, on those occasions there was no loss of life.

Kapitänleutnant Otto Eduard Weddigen died on 18 March 1915 while in command of U-Boat 29. On patrol at Pentland Firth, Scotland, he surfaced after firing a torpedo at H.M.S. Neptune. Unfortunately, it was in front of H.M.S. Dreadnought and before he could submerge it was rammed by the powerful battleship. The U-Boat sank, taking with her the entire crew. Their grave is also the sea.

A full list of over 2000 casualties plus survivors from the four ships can be found on:- www.naval-history.net

Chatham Naval Memorial contains the names of 18615 identified casualties.

Plymouth Naval Memorial contains the names of 23192 identified casualties.

Replies to Comments

In the comments below Sandra Topley asked if anybody had a photograph of her grandfather Thomas Arthur Jobbins, who was one of the sailors that perished on the HMS Abourkir.

Slav replied on 7th January 2016 with a photo. He points out that her grandfather is the sailor on the right.

Comments about this page

Add your own comment

Let’s not forget that some Benfleet men actual survived this terrible event.

W.PARISH was on the Cressy and survived but was wounded.

Further reading.

“Three before breakfast”

A true and dramatic account of how a German U-boat sank three British cruisers in one desperate hour.

ISBN 085937 1689.

Copyright. Alan Coles.

Published by Kenneth Mason, Homewell, Havant, Hampshire.

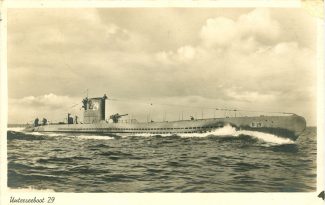

When looking for information, I found your website by accident and in the article: Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen, 1882-1915 – I found a bug. Photo of the U-29 submarine posted in this article.

This photo shows the WWII U-29 type VIIA ship which was built only 24 years later. It was built on August 28, 1936, and entered service on November 16, 1936, sunk on May 5, 1945 in the Baltic Sea.

Weddigen switched from a kerosene-powered U-9 to a more modern oil-powered U27 class ship. Only 4 ships of this class were built in 1912-1914 Kaiserliche Werft, Danzig.

Weddigen received a U27 class ship U-29, built on October 11, 1913.

You can see a diagram of the U27 class in the German Ubootwaffe museum on which Weddigen was sunk. But no photo of these four ships has officially survived to our time. U27,28,29,30.

I am so sorry Sandra; I feel really bad that I failed Your hope; I promise I will do my best and I will look forward to find a picture of Your grandfather; I can only hope this time my friend will not let me down like this…

I don’t know what to say… I feel ashamed…

I must point out that Slav was mistaken, the picture is of Arthur Richard Town. The medal ribbons on both sailors, are from WW1. Thomas was awarded those medals but posthumously. He did not receive 8years LSGC stripes either. The picture must’ve been taken in 1918 or later. Thomas died in 1914. Sandra Topley

Slav, Thank you so very very much. I am amazed and very very grateful. My Father was 2 when Thomas died, and he and his brothers lost their Mother, in 1917, so photographs were the least of their problems. None survived. I have searched and searched and left requests on many sites in the hope of finding one and thanks to you i now know what he looked like, are you descended from the other sailor – what was his name? can i please have your permission to post it on my Ancestry tree – thank you again, Sandra.

Hi Sandra Topley,

I’ve found the picture of Thomas Arthur Jobbins.

Arthur is the one on the right.

I have in my possession a small beaker made from what looks like bone. It has the title HMS HOGUE with an anchor and on the reverse side a sailing ship! All carved over a sea scene with other lighter sailing vessels. Does any one known any thing about this item that my mother gave to me recently?

Tim Green

Hi Tony,

Thank you for this alteration (now made) and the other comments you have added to records of our War Memorial. They are much appreciated as they improve the picture of the person who died.

Regards

Phil

Note that Jennings Arthur service number according to CWGC should be 305498.

Thank you very much for the details regarding the sinking of HMS Aboukir. Both my cousin & myself are always seeking information regarding the death of our Grandfather, John Hogan. There was a knock on effect to our family, as John Hogan left a wife and four children. His wife died from starvation as did one of his daughters (there was no welfare state). His two young sons and surviving daughter were placed in a Catholic orphanage where they suffered. The daughter (my mother) was placed in service in London far away from her brothers in North Shields. The brothers ran away to join their sister in London. One joined the army & the other the Merchant navy. They all had a very hectic second world war but survived.

Does ANYONE have a photograph of my grandfather, Thomas Arthur Jobbins, who was one of the sailors who perished on the HMS Abourkir?

My name is Michael Booth and my family are all from Nottingham. A few months ago I was speaking with my elder brother and the conversation got round to my Uncle John*. He was my dad’s brother and I knew nothing about him. He wasn’t spoken of as I was growing up. He hadn’t done anything wrong but my elder brother told me that my dad was heartbroken at his brother’s death. My brother had a scroll that I downloaded and decided to find out what happened to him and the Hogue. I searched the Internet for days and then found the ‘Benfleet Community Archive’ and an article by Ronnie Pigram. Everthing I wanted to know was in his article and I admit to shedding a tear as I read about my uncle’s fate. Thank you, Ronnie Pigram and the Benfleet Community Archive.

* John Booth

Add a comment about this page